Why OODA Matters for Incident Response

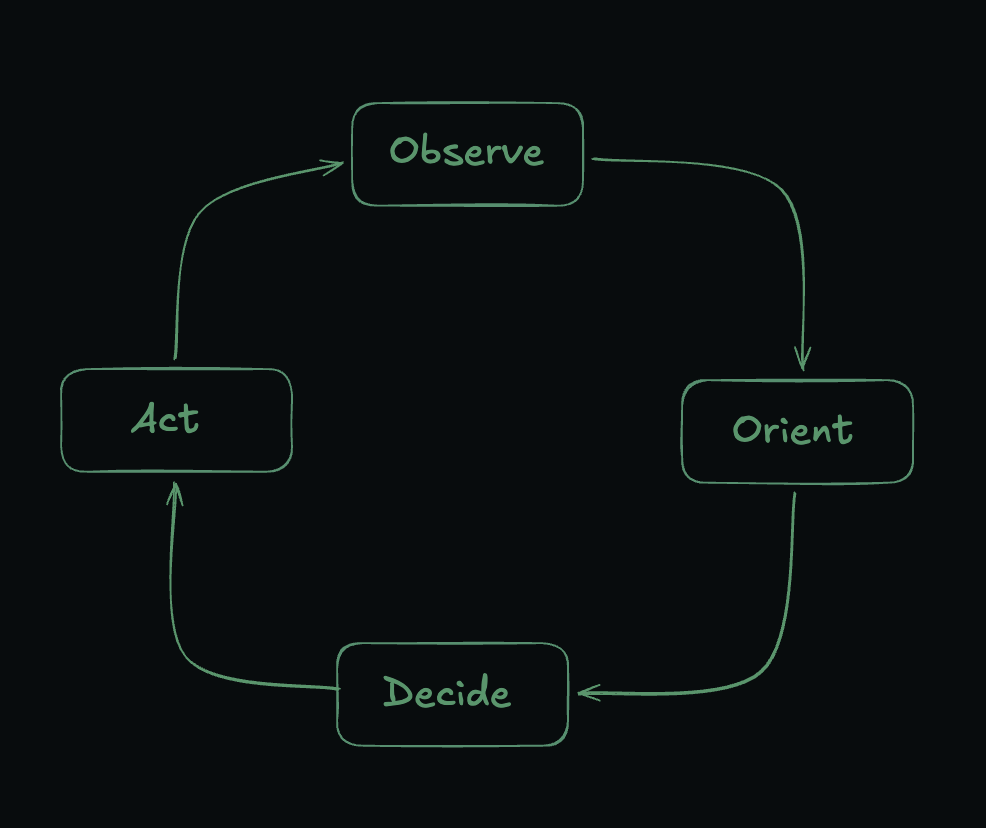

Boyd’s core insight was simple: the entity that can cycle through observe-orient-decide-act loops faster than their adversary gains a compounding advantage. Each completed loop creates new information that feeds the next cycle. Fall behind, and you’re always reacting to outdated conditions. This maps directly to incident response. Threat actors operate on their own OODA loops, probing your defenses, adapting to your responses, and exploiting gaps in your visibility. Your job is to complete your loops faster and more accurately than they complete theirs. By the nature of corporate communications and workflows, adversary OODA loops will be faster/tighter than defensive OODA loops. So the answer is move faster right? Not really. Speed without structure creates chaos, and that’s not productive for anyone. Teams that rush through incidents without deliberate process make mistakes, miss critical context, and often extend the very incidents they’re trying to resolve. OODA gives you a framework for being both fast and methodical.Mapping OODA to Incident Response